For as long as sport has been played fans have been an adored and integral part of the game – football is nothing without them, after all. Fan identities associated with, or defined by, local teams is something that’s proudly and inextricably linked to the core of any sport. Roaring crowds and playful competitiveness inject life into what is otherwise, quite frankly, a group of men or women kicking a ball around for 90 minutes.

But the nature of the fan – how they experience the game and their relationship with their football club - is gradually changing and evolving as a result of the commercialisation and globalisation of sport. While purists of the game will inevitably argue that this compromises authenticity and tradition, the commodification of football has given birth to the new, modern fan – and they’re able to watch, engage and actively invest in any team, in any league, in any given sport around the world. Or at least that’s the aim.

Adam Silver, the current commissioner of the NBA in the US, has previously said: “Probably 99.5 per cent of our fans are never going to have the opportunity to go into an NBA arena, and I think the notion that you can become part of that experience is phenomenal.” The stats – and the shift to online communication, exacerbated by COVID-19 – support this move towards the new ‘absent but present’ fan.

Of course, the traditional fan still exists, and sits – quite literally – at the centre of the club, visiting matches, buying brochures and refusing to engage with social media. But this is becoming an increasingly small proportion of fans globally; around 70% of online traffic to the biggest Premier League clubs, for example, comes from international markets, and this is only expected to grow with time.

It is, perhaps unsurprisingly, US sport that has spearheaded this successful shift towards the modern fan and capitalised on the huge profits to be made from making the ‘Big Three’ – baseball (MLB), American football (NFL), and basketball (NBA) – typically considered almost exclusively American sports, accessible to fans globally. The prime example of this is, of course, American football’s annual Super Bowl, the pinnacle of the NFL which has undoubtedly transcended its sport and become an iconic event in itself.

Renowned for its half-time shows, which have their own dedicated Wikipedia page and typically last 30 minutes, the event features performances from the likes of Beyonce, Coldplay and Shakira on a stage that’s often compared to Glastonbury. The venue itself changes every year, highlighting how the spectacle is not tied to a specific location but performed primarily for an online audience – having had a staggering 96.4 million viewers this year. When the Rolling Stones headlined the event in 2006, more fans – be they sport or music – tuned in to watch than the Oscars, Grammys and Emmy Awards combined that year. With the exception of major tournaments, such as the Olympics and the FIFA World Cup, the scale of the event is unparalleled in sport.

Part of the overwhelming success of the Super Bowl, in terms of fan engagement, is this unique blend of music, entertainment and sport. While this does, arguably, detract from the sport itself, it engages those who wouldn’t otherwise be interested in it. Given that American football is, primarily, an American sport (the clue’s in the name), it’s provided a platform for viewers worldwide. As Mark Waller of the NFL previously said: “International [American] football fans are born on the first Sunday of each February” – the day of the Super Bowl. Working with corporate sponsors to host viewing parties in every continent, and Western hospitality venues to host buffet socials, every effort is exerted to ensure fans aren’t only watching the Super Bowl, but are doing so in an environment that emulates that of a sports stadium.

While there is often a distinction to be made between in-person and online fans, and an increasing tension between their hopes and desires for the club, part of engaging fans globally is striving to create a shared sense of experience. Those watching the 2021 Super Bowl could, for the first time, engage in 5G interactive experiences, switching between several camera angles and watching with others online in a shared space, therefore trying to replicate the live experience as much as is physically possible from afar.

The Super Bowl Experience, where fans can visit one of the locations that’s hosted the event, is a further way in which the NFL endeavours to immerse fans in the sport. Separate to the event itself, it allows fans to meet NFL players and legends, run a 40-yard-dash and immerse themselves in the world of American football whenever they happen to be passing the streets of LA, encouraging more general, online engagement through a heightened interest in the sport, as well as the interactive experiences on offer via LED screens.

By trying to create a global community, American sports leagues are encouraging fans worldwide to engage online in various ways beyond the game. On October 12th 2021, ahead of the MLB World Series between the Atlanta Braves and Houston Astros, MLB’s official Twitter handle sent out a request in four languages – English, Spanish, Japanese, and Korean – for fans to reply in any language about what baseball means to them, using the #PostcardsFromHomePlate hashtag. Fans responded in 31 different languages across 53 markets – representing every continent except Antarctica. This not only helped break down barriers between fans speaking different languages from different corners of the world, but also helped eradicate the outdated notion amongst many sports fans that baseball is a sport for America, and Americans, only.

53 countries. 31 languages used. 1 love for the game. #PostcardsFromHomePlate pic.twitter.com/hsHr1ly25O

— MLB (@MLB) October 30, 2021

Rather than social media, the NBA turned to another form of online entertainment amongst young people – Netflix. The hugely successful docu-series, ‘The Last Dance’ revisits the life of NBA legend Michael Jordan on an unusually personal and intimate level, capitalising on his fame beyond basketball and America to entice a new audience. Presented in a way that is somehow interesting and insightful to both avid basketball fans and those who know nothing about the sport, like myself, it has encapsulated sports (and Netflix) fans around the world, broadening the NBA’s reach and fanbase, and becoming the world’s most in-demand documentary in the process.

The ten-part series is widely regarded as contributing towards the continued growth of the game globally, particularly in China and India, where figures have soared in recent years. While this may be less obvious fan engagement than using social media, the NBA and the Chicago Bulls played their part in providing footage and access to off-limits locations – they were aware of the untouched audience the show could, and did, tap into.

But for all the innovative ways of engaging fully grown adults in a brand new sport, clubs and organisations recognise, much like the traditional fan, that there’s nothing quite like the real deal when it comes to live sport. The NBA recently announced that they will be opening the first of six ‘DreamCourts Preview Centres’ in China next year, in Suzhou. The centres will feature restaurants, shops and interactive games and will be developed by NBA China in an attempt to continue the growth of the game across Asia.

The emergence of single leagues played across several continents, which the NFL has also seen, with several games played in the UK every year, offers a whole new and uncertain dimension to the globalisation of the fan experience. Will the ‘international’ experience become increasingly merged with that of more traditional, match-attending fans, with league games taking place all around the world? Would this be beneficial or detrimental to sport?

It’s probably too early to tell. What we do know, however, is that a few decades ago the rest of the world showed little interest in America’s ‘Big Three’, but the powerful fan engagement strategies of clubs and leagues across the nation have generated global interest in sports that are still, predominantly, played on American soil. Breath-taking events, the rise of social media and the wholehearted turn to online communication due to the pandemic all contribute – but whatever the reason, the sports are spreading like wildfires.

But it’s not just America that sees the promise and potential in catering towards an international audience. In fact, many other markets see the US as a target area of growth – with a fierce passion for sport and a whopping population of 329 million, it seems a logical first step. A nation with a rapidly rising interest in football, or soccer, having recently overtaken ice hockey to become the fourth most popular sport, the US is a prime market for England’s Premier League.

The new Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, for example, has been designed to encourage the active involvement of US sports fans, even if they’re not, yet, converted soccer fans. Replacing White Hart Lane, the London club’s beloved home for 118 years, it marks the first purpose-built home for NFL in Europe, and will host a minimum of two games a year over a ten-year partnership. The agreement, which of course encourages an interest in American football games across the UK, also ensures that “the NFL embraces the community of Tottenham Hotspur”, as it claims on the club’s website. By connecting with the league, the club are effectively inserting themselves into the NFL fanbase, having more exposure to the US market.

Furthermore, the club have an ongoing partnership with MLS side San Jose Earthquakes, drawing already existing soccer fans into the prestigious Premier League, the sport’s most successful domestic league. Their engagement strategies, therefore, focus on both current soccer fans and generic sports fans who have the potential to be converted.

They aren’t the only English club with a desire to expand across the Atlantic, either. Several top clubs have partnered with an MLS side in recent years; Arsenal entered into an agreement with the Colorado Rapids in 2007, and Manchester City’s owners – the City Football Group – formed a new MLS franchise, New York City Football Club, in 2013. With these clubs eager to grow their foothold in the US, and America keen for the world’s most popular sport to take hold in the world’s maddest sport nation, the partnerships provide mutual benefits in what is, essentially, a shared goal. The Premier League is as popular as the MLS in the States today, with 20% of 18-24 year olds in the country showing an active interest in the ever-growing game.

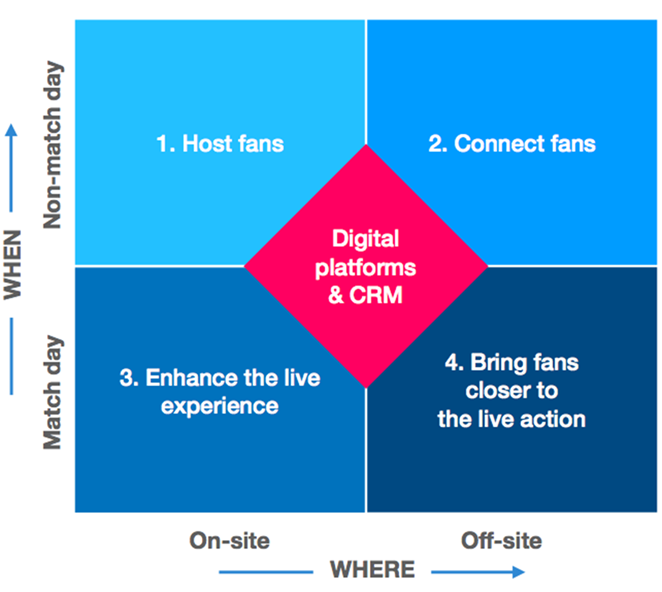

Adam Fields, Head of Global Fan Engagement at Chelsea FC, claims that American sports fans are a key area of focus for the biggest Premier League clubs, but that marketing to them requires a localised approach, separate from that of England’s, which focuses on the passionate and broadly knowledgeable fan. Speaking at the Digital Transformation Conference in London in 2019, Field outlined how it is “a major challenge to communicate at scale but still have an impact with individuals”, but claimed that it’s what’s necessary in order to expand into the most profitable market.

Amazon Prime’s ‘All or Nothing’ series, which has delved into the dressing rooms of Tottenham Hotspur, Manchester City, and will tackle Arsenal next year, has also formed a part of the fan engagement strategy of the clubs who opened their doors to the multi-billion pound company. With Prime Video memberships owned by nearly 200 million people across 22 different countries, exposure as a result of the agreement was unquestionable. The docu-series has, however, been criticised for its blatant focus on an international audience, designed to draw in new fans, perhaps overlooking existing ones in the process.

But the online forms of engagement are not the only ways the UK is closely following in the footsteps of the US. The match-day experience in the Premier League is gradually changing, and commercialising, extending far beyond the 90 minutes of football. Tottenham’s stadium is the prime example of this; with 60 food and drink outlets from a “diverse” background, nine floors, pop-up experiences and various promotions and competitions dotted around the stadium, the club is doing all it can to encourage fans to immerse themselves in entertainment around the match. This entertainment, much like with the Super Bowl, transcends gameday itself – the ‘Tottenham Experience’, to use the phrasing from Tottenham’s own website, includes stadium tours, a skywalk, and the UK’s first controlled drop from a stadium. This represents what will likely become a far broader shift to an entertainment-based fan experience at Premier League clubs with time, as this ultimately increases profitability.

Likewise, the recent controversies surrounding whether or not to extend the half-time of Premier League matches to 25 minutes, from the current 15, feeds into the wider debate about this shift towards entertainment-based sport in England. With the clear purpose of accommodating more half-time shows, the discussion demonstrates how English football’s governing bodies are eager to incorporate more activities around the game for the profit, and wider audience, they would likely appeal to.

Fans, however, were deeply sceptical of the idea, slamming it as shameless commercialism that would continue to chip away at the authenticity of the game, and so the concept has been dropped, for now. For all the obsession over financial and international growth, football does not want to disenchant itself from the royal, loyal fan – the short-lived European Super League was enough to prove that.

The natural push for widening one’s fanbase, therefore, must not come at the expense of isolating the traditional fan; all activity has to bear in mind these overlapping, but in many ways contradictory, audiences. Therein lies the difficulty of the task.