Gambling in sports is a notoriously controversial and divided topic, particularly in terms of the exposure brands can receive from sponsoring Premier League clubs. While the issue is, of course, inseparable from the moral and ethical debate that surrounds it, UCFB’s Market Research and Insights Executive Adam Brenton explores the effectiveness of sponsorship brands in football, why they struggle to engage with fans and why the should reconsider working with football clubs altogether. Here, he summarises his Master’s dissertation on the topic…

Main Findings

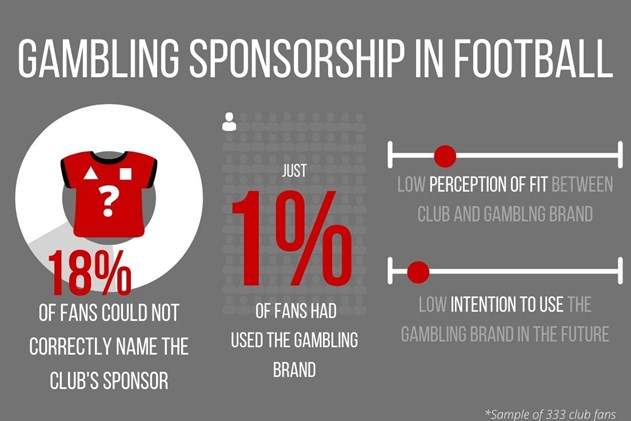

Fans cannot distinctively recall the gambling brand, perhaps due to gambling brand sponsorship being such a crowded market place. Fans also do not use the gambling brand, and they don’t intend to in the future; they do not feel gambling brands fit their club values.

Therefore, gambling brands have a poor relationship with the fans. Sponsors are meant to build and enhance relationships with fans and clubs to create an enhanced sporting experience. Instead, when a gambling brand is present, the relationship is purely transactional: it’s all about the money. Gambling brands just want exposure. They don’t care about who the club is, or who the fans are, just where they can get their logo viewed.

Achieving sponsorship effectiveness is currently known to be influenced by cross-industry standardised factors – the type of brand sponsoring is not known to impact the success of the sponsorship. Fans become aware of the sponsor and therefore transfer their positive imagery of the club towards the brand (Dalakas and Lavin, 2005). Researchers have found fans are then more likely to have previously purchased the sponsors products (Zaharia et al, 2016) or have a higher intent to purchase them in the future (Koronios et al, 2016). Engagement with the sponsoring brand is increased depending on how committed the fan is to their team (Tsordia et al, 2018), and how congruent the fan perceives the relationship between club and brand (Wakefield, Becker-Olsen and Cornwell, 2007). However, the results from this study differ from this standardised framework suggesting that when the sponsoring brand is a gambling company, different relationships are present.

The summary will begin by discussing the significance of the relationships between sponsor recall, future buying intention and previous purchase history and the implications the results have for the sponsor (Dafabet), the (unnamed) Championship club, and sports industry officials. It will conclude by calling for a revision of current theory before analysing Dafabet’s sponsorship strategy.

SPONSOR RECALL

When the study was completed in the 2019/20 season, the majority of fans were able to recall the sponsor with 82% of fans correctly naming Dafabet, showing front-of-jersey sponsorship to be a successful asset in achieving brand awareness. However, this score is lower on average when compared to other similar studies - Zaharia et al (2016) found 94% of Chelsea fans were able to achieve correct sponsor recall.

Furthermore, Dafabet and other competing brands involved in sport sponsorship should be concerned it is hard to achieve true brand recognition in a crowded marketplace. In the Premier League 60% of clubs have a gambling brand as their title front-of-shirt sponsor and this is even higher in the Championship at 73% (Statista, 2020). Brands look to sponsorship as a way to differentiate from their competitors (Cornwell et al, 2001; Cornwell et al, 2005) yet given gambling brands are so prevalent in this space, gambling companies should be aware of these findings that indicate there are challenges in achieving distinction from rival brands.

Specifically, the recall rates for under 18s are worrying. 80% of under 18s were able to recall Dafabet as a sponsor. Gambling is illegal for under 18s and the sports industry has faced criticism for publicising, normalising, and encouraging gambling to its audience that consists of younger generations (Lamont, Hing and Gainsbury, 2011). As such, measures have been put in place such as removing gambling sponsors from child-sized replica shirts.

FUTURE BUYING INTENTION

While identified fans were largely successful in recalling the sponsor, there was not a correlation found between fan identification and future buying intention. This rejects what is known from Koronios et al (2016) and Aaker (1991) that identified fans, who recall a sponsor are more inclined to purchase the product. This suggests when a gambling brand is present such simple assumptions cannot be made.

The fans who are aware of the sponsor are disinclined to convert into a customer. Plus, even highly passionate fans - that a sponsoring brand could expect to want to purchase their product - do not have this intention. This demonstrates the complexities involved in gambling sponsorship as personal beliefs and motivations surrounding gambling behaviour make it harder to convert fans into customers. Gambling is not a necessity and using a gambling service derives from a personal desire. As such, the pool of interested customers is a comparatively small audience compared to the industries of other sponsoring brands in UK football. Fans will display a higher intent to purchase products from non-gambling brands as their products provide fundamental services for modern day consumers such as cars, smartphones, and air travel, for example. Dafabet face the challenge of not just converting individuals to their brand, but also to engage with the behaviour of their industry.

However, sports industry officials and commentators will be concerned that under 18s expressed some intention to purchase Dafabet’s products. While the score was lower than the average and second lowest out of all age categories, it can be argued an ideal would be for the under 18s age group to express no intention to purchase at all.

Further, typically gambling audiences are predominantly male (Hunter, Shorter and Griffiths, 2012), the study finds females to express more of an intention to purchase Dafabet’s products. This insight suggests Dafabet could do more to engage females in their products so that their intention to purchase is converted into an actual transaction.

PREVIOUS PURCHASE HISTORY

The most alarming finding from this data is that only three respondents out of the 285 in the sample have stated they have used Dafabet’s services since the bookmaker became a sponsor of the club. This is 1% of the sample size. In comparison to similar studies, such as Zaharia et al (2016) who found 62% of Chelsea FC fans had purchased the title sponsor’s products, this is much lower and proves that Dafabet are failing to acquire customers from the club’s fan base, meaning that the fans are not fully engaged with the Dafabet brand. When expected aims of sport sponsorship are considered - that fans of clubs are converted into customers of the brand (Dekhil, 2010) - Dafabet would have an extremely poor return on investment. This calls in to question Dafabet’s relationship with the fans – something that can be measured through sponsorship fit (Gwinner and Bennett, 2008).

Sponsorship fit was perceived to be low, with an average index score of 2.032. This supports views from Cornwell (2008) that gambling brands do not display good fit with sports clubs and suggests that the fans in general do not feel much affinity towards the gambling brand as a sponsor. Previous research says more identified fans usually perceive this fit to be higher (Tsordia et al, 2018), but this research finds no such significant relationship. From this we can deduce that in fact fans do not approve of having a gambling company as a sponsor, and even the most committed of fans are not in support of having a gambling sponsor.

GAMBLING BRANDS

If gambling brands want to achieve success with fans, and solve the issues discussed, it could be suggested they invest in activation strategies to engage with these fans. Zaharia et al (2016) state sponsorship activity needs to connect with fans beyond merely an awareness stage with sponsorship activations being a great tool to build, enhance or alter a brand image (Gwinner, 1997). Activation methods incorporated as part of CSR strategies with social objectives are a successful way to communicate brand messaging and engage with fans to improve brand equity and sponsorship fit (Zaharia et al, 2016; Tsordia et al, 2018). Improving sponsorship fit is significant because, as this study and others (Speed and Thompson, 2000; Koronios et al, 2016) show, this can help increase future buying intention. Activations will also help to improve their relationship with the fans which will make fans more able to distinctly recognise the brand over their competitors (Scott, 2017).

However, sponsorship activation methods can be extremely costly. Dafabet’s sponsorship of the club reportedly cost £3m (Geey, 2019). This is the fee paid solely for sponsorship rights. Additional activation of sponsorships are organized at the cost of the brand. Meenaghan (1994) reports brands can often pay sums equal to or greater than the initial rights fee on further activation.

It is therefore questioned whether gambling brands are concerned enough to invest in further activations. As discussed in the literature review (Danson, 2010; Friend, 2018), their aims of partnership with Premier League and Championship clubs appear to be not to achieve sales from fans specifically, but yet to use the club as a vehicle for general exposure.

The findings prove gambling brands approach sponsorship with a unique strategy. It is shown companies are not focussed on building relationships with fans, or converting fans into customers, yet simply are trying to achieve raw publicity. This strategy goes against modern sponsorship arguments that brands should prioritise finding a fitting relationship and engaging with fans rather than just publicity (Lachowetz, 2002). But we know that even if a fan is aware of a sponsor, there are social, economic or demographic factors that could prevent their engagement with the brand (Tsordia et al, 2018). This is definitely the case with the gambling industry where age, religion, finances and personal beliefs prevent people engaging with the behaviour of the industry, and consequently with the brand. In the most extreme circumstances, people form strong opinions in opposition of the gambling industry and consequently oppose the brand’s association with the club.

Therefore, it can be concluded gambling companies will always face some challenges in fully engaging a specific club’s fans. Given the largely unreceptive response, in part due to the controversies of the topic, it is perhaps best for gambling brands to refrain from using football clubs to promote their brand. There are, of course, many moral and ethical issues associated with this that also support banning such brands from mass public exposure through Premier League clubs.